Laser Lithotripsy in Small Animal Veterinary Medicine

Clinical Connections – Summer 2016

RVC small animal referrals is the only veterinary service in the UK offering laser lithotripsy treatment for urolithiasis. Laser energy is provided within treatments via a fine (200-550 µm core diameter, with a coating sheath) silica quartz fibre which can be advanced through the working channel of an endoscope to provide targeted application of energy directly onto stones, causing fragmentation.

As well as laser lithotripsy, the RVC team performs cystoscopic laser ablation of ectopic ureters. The laser can also be used for the removal of polyps and biopsy of neoplastic lesions within the urinary tract.

Although the resistance of different stone types to fragmentation is variable, essentially all types of stone can be treated by laser lithotripsy. The laser of choice for intracorporal use is a holmium:YAG laser, which emits light at an infrared wavelength of 2 100 nm. Since this is not visible, it is accompanied by an ‘aiming beam’ of visible light.

Laser lithotripsy is performed using cystoscopic guidance in an aseptic manner. Rigid cystoscopes, of various sizes, are preferred for use in female dogs and cats because of the superior images that are obtained compared with flexible fibre-optic endoscopes. These are used in male dogs but it is currently only typically possible to perform endoscopy on male dogs weighing more than about 8-10 kg as the endoscopes used are about 2.7 mm in diameter. Although smaller flexible endoscopes are being developed, smaller male dogs and male cats cannot currently be treated with laser lithotripsy.

Treatment of uroliths by laser lithotripsy is very successful, particularly in female animals. In male dogs, success rates are also high at approximately 80%, results that are comparable with success rates for complete stone removal by cystotomy.

The success of lithotripsy in male dogs is limited by the poorer visualisation provided by the flexible endoscopes and by swelling of the urethral mucosa. The swelling limits the number of times that the urethroscope can be passed into the bladder. In some cases, any remaining uroliths can be successfully removed during a second procedure a few days after the first.

Case Study 1

- GEMMA: Gemma, a 12-year old, female spayed cross breed, was referred to the QMHA in August this year for non-surgical treatment of a urocystolith. The urolith was detected incidentally 18 months prior to presentation but, since Gemma was not showing clinical signs, treatment was not undertaken initially. However, in the intervening period she had two episodes of lower urinary tract signs, possibly related to urinary tract infections, and so it was recommended that the stone be removed.

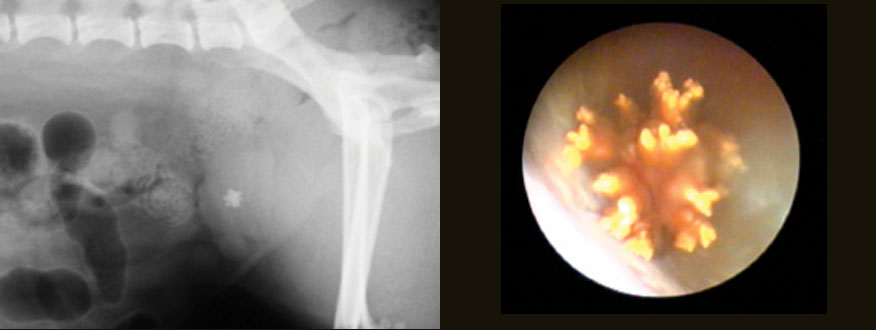

Physical examination of Gemma was essentially unremarkable, who weighed 7.5kg. Abdominal radiographs revealed a single, spiculated, urolith that was highly radiopaque (figure 1). Small mineral opacities were also noted in the area of the kidneys, a finding which was confirmed ultrasonographically.

The radiographic appearance of the urolith, together with the patient’s signalment, was suggestive of a calcium oxalate stone. A urine sample was collected by cystocentesis and this showed 2+ blood and >3+ protein with an inactive sediment and no crystals, urine culture was negative. Her urine specific gravity was 1.041. Since calcium oxalate stones are not amenable to medical dissolution it was decided that removal of Gemma’s stone by laser lithotripsy would be the ideal treatment, eliminating the need for abdominal surgery.

Gemma was anaesthetised and positioned in dorsal recumbency. A small rigid cystoscope was passed along the urethra into the bladder and the stone visualised in the bladder neck (figure 2). Laser lithotripsy was then performed with a 20W Holmium:YAG laser using a silicone quartz fibre passed through the working channel of the endoscope. This resulted in rapid fragmentation of the stone into pieces that were small enough to be removed by voiding urohydropulsion.

Once cystoscopic examination of the urethra and bladder did not reveal any remaining urolith fragments, post-procedural radiographs were performed to confirm that the whole urolith had been successfully removed. She was given a single dose of buprenorphine post-procedurally and was discharged the next morning with a 5-day course of carprofen. Analysis of the stone fragments confirmed that it was composed of calcium oxalate. Gemma was switched to a moist therapeutic diet (Royal Canin Veterinary Urinary S/O in this case) in an attempt to reduce her urine specific gravity and reduce the risk for stone recurrence.

Case Study 2

- LOTTIE: Lottie, a three-month-old female entire fox terrier weighing 3.65 kg was referred to the Emergency and Critical Care for management of urethral obstruction. She had been seen by her referring veterinary surgeon three days prior to referral for lower urinary tract signs and was treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate and meloxicam at appropriate doses. However, the clinical signs had not resolved.

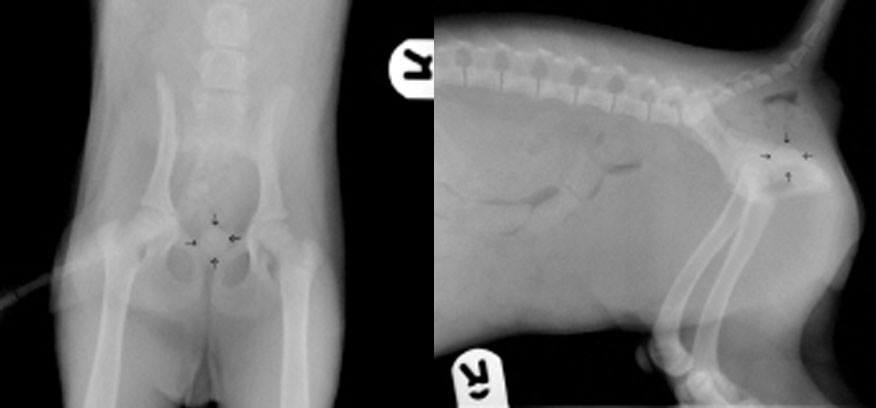

On presentation at the QMHA Lottie appeared quiet and mildly dehydrated. She was repeatedly straining to urinate but very little was passed. Her bladder was large and firm on palpation. A point-of-care analyser was used to perform a plasma biochemistry panel and showed that she was not hyperkalaemic or azotaemic. Abdominal radiographs were obtained under light sedation (with butorphanol) and these revealed a single 9mm diameter, spherical, radiopaque urolith in the proximal urethra (figure 3).

Plans were made to retropulse the urolith back into the bladder by flushing saline through a urethral catheter. However, at some point between obtaining the radiographs and her returning to the intensive care unit, the stone dislodged spontaneously and Lottie immediately passed a large volume of urine. On repeated palpation of the abdomen the bladder was small and soft and a marble sized hard spherical structure could be palpated within it. A sample of the voided urine was examined; numerous leukocytes, a few erythrocytes and many struvite crystals were observed. Lottie was treated overnight with intravenous fluids and antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin-clavulanate) administered intravenously.

Laser lithotripsy was performed the following morning. Although the patient’s age and the urinalysis findings made it most likely that the urolith was composed of struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate), which could have been managed medically (with antibiotic and dietary therapy), the owners were concerned about the risk of re-obstruction, and so preferred that the stone be removed.

Given her young age, they were keen to avoid a cystotomy if possible. With Lottie under anaesthesia, laser lithotripsy and voiding was performed in a similar manner to that described above. When the cystoscope was first passed into her bladder, a sample of urine was collected aseptically for culture. Her stone was a little more resistant to fragmentation than Gemma’s, and initially the laser simply ‘drilled’ multiple holes into the stone but following eventual fragmentation the stone was successfully removed. Post-procedural radiographs showed no residual stone fragments.

Lottie’s recovery was uneventful. There was no microbial growth from the urine culture, presumably because appropriate antibiotic therapy had been initiated prior to referral. Antibiotic therapy was continued for three weeks following the lithotripsy to ensure elimination of the urinary tract infection. She was also treated for one month with a therapeutic diet for struvite stone dissolution (in this instance Hills Canine S/D) before being returned to her usual diet.

Although Hill’s S/D is not generally recommended for use in growing puppies (due to its acidifying nature and low protein content) it was considered that its short-term use in a small breed dog was unlikely to be detrimental and that feeding this would minimise the risk of immediate stone recurrence.

During subsequent follow-up visits, it has emerged that Lottie is incontinent which is likely to have predisposed her to develop urinary tract infections. Incontinence was not reported by the owners during the first visit as they had considered that her pattern of urination was due to poor house-training.

Although cystoscopy is an excellent tool for documenting whether ureters are ectopic or not, unfortunately, since there was no history of incontinence at the time Lottie was cystoscoped, this was not something that was systematically evaluated - although ectopic ureteral openings were not noted during lithotripsy.

Subsequently, an excretory urogram confirmed that both ureters open in normal positions and Lottie has been diagnosed with congenital urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence.

Her incontinence has responded well to treatment with phenylpropanolamine and she is being regularly monitored by her referring veterinary surgeon for recurrent urinary tract infections.

Sign up to get Clinical Connections in your inbox www.rvc.ac.uk/clinical-connections